VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOLUnlike the Japanese onsen baths, where the bathroom was an intimate activity in contact with nature, or the Incas, where the Inca bath was associated with religious ceremonies, in the Roman Empire baths were the social activity per excellence. The baths not only served a hygienic function, but it was a social leveler that congregated men and women, slaves and free citizens. They were also associated with pleasure and in big cities like Rome, bathing often implied promiscuity. Therefore, early Christians and philosophers refused to participate in this activity and went to bathe just twice a month. The relationship with the landscape existed, but insted of locating the baths in a special place in the landscape, as in the cases mentioned above, the landscape was created artificially to the delight of bathers.

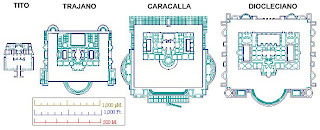

In the case of the baths of Caracalla, the larger thermae that survive until today and the second largest ever built, after Diocletian ("thermae" comes from the Greek word "thermos" (θερμός), which means "hot").

The complex was begun by the emperor Septimius Severus in 206 AD and completed by Caracalla between 212-217 AD. Subsequently, other emperors such as Alessandro Severo and Elagabal completed or repaired the building. The building was destroyed by an earthquake in 847, although from 537 it could not be used anymore as water channels were destroyed by war.

The Baths in ruins in the seventeenth century, buried several meters.

The Baths in ruins in the seventeenth century, buried several meters.Engraving by Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778)

The complex covers an area of 13 hectares and is located at the beginning of the Appian Way. The main building was 228 m long by 166 m wide and 38.5 m tall.

Besides the baths, which could accommodate up to 1700 bathers, it included social spaces, libraries and even a small stadium.

The site was defined by a rectangular fence. The design, as in many other cases in the Roman architecture, followed a symmetrical layout.

The main entrance was located in the northeast, flanked by arcades on two levels containing commercial stands. After passing through the entrance arcade, there were gardens that preceded the main building. Upon entering the visitor reached the dressing room (apodytera), and after taking off his clothes he left them on a shelf. Later he worked out at the gym (palestra) or received a massage in one of the nearby rooms. The thermae had three types of baths: cold, hot and warm.

The first one was the Frigidarium, a large living room containing cold baths that had a huge outdoor pool or natatio. In the middle of the building was the Tepidarium, where the warm baths were located. Then the users went to the caldarium, a kind of saunas, whose walls were heated through terracotta pipes and whose cylindrical shape was covered by a cupola overlooked the whole complex.

The first one was the Frigidarium, a large living room containing cold baths that had a huge outdoor pool or natatio. In the middle of the building was the Tepidarium, where the warm baths were located. Then the users went to the caldarium, a kind of saunas, whose walls were heated through terracotta pipes and whose cylindrical shape was covered by a cupola overlooked the whole complex. On either side were two large semicircular protrusions that were the libraries. In the background the stadium was located, with seats only on one side, hiding behind itself the huge cisterns.

One aspect that caught my attention was the impressive scale of the building. This was not a temple or a palace, was a public facility. However, the impressive monumentality of the scale makes it clear that the architecture was used as a symbolic instrument of imperial power.

The building system combined the use of baked brick with concrete (opus caementicium) which was a mixture of small pebbles and sand and lime mortar. But even more impressive was the elaborated water system which served the baths.

The water was brought from the springs of Subiaco, 100 km from Rome, through the aqueduct Aqua Marcia and from there it was supplied by a special branch called Aqua Antoniniana. The water arrived to a huge tank divided into 18 compartments and a capacity of 80,000 m3. From there it was distributed by tubes and crossed the gardens toward the building.

There were three networks of tunnels, built to facilitate inspection and maintenance of the facilities: water, sewage and provision of wood, which was used in about 50 furnaces to heat the water.

The interior of the thermae was outstanding. The outdoor pool or natatio was decorated with four granite columns. There were also large bronze mirrors to reflect the sunlight. The walls were covered in marble and decorated with frescoes, and hundreds of statues were located in niches at various levels.

3D Image courtesy of Altar4 Multimedia

The floors were covered with black and white mosaics, some of which can still be seen at the site.

The landscape design was remarkable, the gardens surrounding the building followed geometric patterns and included statues, fountains and places for meeting and conversation.

In the twentieth century, in 1911, the baths were replicated in the Pennsylvania Station in New York, giving a more tangible idea of the grandeur of this impressive complex.

Today, besides being a major tourist attraction, the thermae is being iused n the last decades as an incomparable venue for cultural performances, theater and musicals .

Documentary on History Channel and the Caracalla Baths

To view a video of our visit, click here

Luciano Pavarotti at the Baths of Caracalla with Dolores O'Riordan, from the Cranberries, singing Ave Maria

SEE ALSO:

- Baths of the Inca, Tambomachay, Cusco, Peru.

- Baths in Kurama, Kyoto, Japan

- Garden of Fine Arts, Kyoto, Japan. Tadao Ando

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar